Perez M. Stewart and H. Ives Smith were prolific developers on the Upper West Side in the last quarter of the 19th century, erecting dozens of high-end rowhouses. In 1897 Stewart & Ives hired architect Clarence F. True to design a row of seven residences at 305 through 317 West 107th Street. Completed in 1898, True designed them in a balanced A-B-C-D-C-B-A plan.

The centerpiece, 311 West 107th Street, was 20-feet wide and, like its siblings, five stories tall. Faced in gray brick and trimmed in limestone, its lower three floors were bowed, providing a stone-railed balcony to the fourth floor. A graceful French-style balcony fronted the French windows of the second floor. The fifth floor took the form of a slate shingled mansard pierced with two arched dormers.

On May 7, 1899, the New-York Tribune reported that Stewart & Ives had sold 309 and 311 West 107th Street to "a well-known merchant." Benjamin Stern, with his two brothers, Louis and Isaac, owned the Stern Brothers department store on West 23rd Street. Just before buying these two houses, according to the article, he had purchased several other dwellings on the Upper West Side "for investment."

Stern rented 311 West 107th Street for two years before selling it in September 1902 to Edward and Regina Steindler. Steindler's life was worthy of a Horatio Alger novel. Orphaned at four years old, he lived in the Cleveland Orphan Asylum until he was 12. The pre-teen traveled to New York City and got a job as an errand boy in a tie factory. He slowly rose through the company to be a "commercial traveller" (today's traveling salesman), "getting a high salary," according to the New-York Tribune later.

In 1893 he organized the New York Curtain Company. It "arranges advertisements for theatre curtains," described The New York Times. (The stage curtains of vaudeville theaters were slathered billboard-like with advertisements.) Steindler was also president of the Block Light Company and of the American Paste Company. "He is also interested in mines, and is said to be the second largest individual owner of mines in the Dominion of Canada," according to the New-York Tribune in 1907.

Regina was known to her family and friends as Regi. Moving into the house with the Steindlers were Regina's parents, Louis and Sarah Franke. Louis Franke was a commission merchant. When he was summoned to testify in a case about water rights upstate in 1903, Franke mentioned, "I live with my son-in-law, 311 West 107th Street, near Riverside Drive; a very fine house."

As well-to-do families left New York City to spend the summer months at country homes or resorts, the men often stayed back to attend business. They would see their families on the weekends. And so, when The New York Times reported on the "expected August rush to the Catskills" on August 9, 1903, among the arrivals at the Hotel Kaaterskill were "Mrs. Edward Steindler" and "Mrs. Louis Franke."

Although the Steindlers had no children, they gave a debutante dance in 1906 for Lola P. Kalman, the daughter of Regina's sister. On April 8, the New York Herald reported that "thirty young people" attended.

On May 17, 1907, Edward and Regina boarded the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria to France. On the afternoon of June 2, they and eight other Americans who were staying at the Elysée Palace Hotel in Paris decided to motor to Versailles for lunch. They took three cars, one of which was operated by Edward Steindler. The New York Times reported, "While the Americans were traveling at an easy rate through the Bois de Boulogne, a heavy racing car bore rapidly down upon the party. Mr. Steindler turned out too late and the racing car cut his car nearly in half."

The New-York Tribune reported, "Mrs. Steindler was picked up in a semi-conscious condition and taken to her hotel." The article said she was "severely injured." The Sun noted, "Mr. Steindler will prosecute Dodey, the racer who was driving the automobile which ran into him." In reporting on the accident, the New-York Tribune parenthetically mentioned, "Mr. Steindler was the largest contributor to a fund for building the Training School for Nurses attached to Lebanon Hospital, of which he is treasurer."

Regina recovered and back home in New York the couple resumed their philanthropic work. In the summer of 1910, The New York Sun reported on the upcoming Orphans Automobile Day. The annual event took Manhattan orphans on a day trip to Coney Island. The article titled, "Committee Needs More Cars For Orphans Day," mentioned, "The latest offers of cars include four sight seeing cars donated by Edward Steindler of 311 West 107th street, who more than duplicated his contribution of last year."

By then, Steindler had expanded his advertising business into the new motion picture industry. Among his various positions, he was president of the Moving Picture Advertising Company.

On April 10, 1912, the 49-year-old suffered a fatal heart attack in the West 107th Street house. Regina took over the reins of at least one corporation and the following year she was listed as a director in the Dorchester-Riverside Company.

Regina Steindler's wealth was reflected in a notice she posted in the "Lost and Found" section of The New York Times on October 18, 1914: "Liberal reward, diamond and pearl bracelet lost in taxicab Thursday night from Cort Theatre to 311 West 107th st." The item was, in fact, a collar, described by police as containing, "sixty-four diamonds set singly, ninety-six in clusters, and thirty-one pearls."

Two months later, on December 15, two detectives arrested Harry D. Koenig and Frederick Young as they attempted to pawn the item. Koenig told the police he found it between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive, "and, needing money now, had determined to pawn it." The New York Times reported, "Mrs. Steinaller [sic] was overjoyed to recover the ornament."

The near-loss was not enough to make Regina more careful. A notice in The New York Times on March 11, 1916 read, "$200.00 reward [for] return of diamond platinum hairpin, tortoise shell prongs, hinges of gold, lost Feb. 25 between Metropolitan Opera House and 311 West 107th St." Regina's offered reward would translate to just under $6,000 in 2025.

Louis Franke died in the house on March 24, 1922 and his funeral was held there on the 26th. Five years later, on October 24, 1927, Sarah Franke died. Her funeral, too, was held in the drawing room.

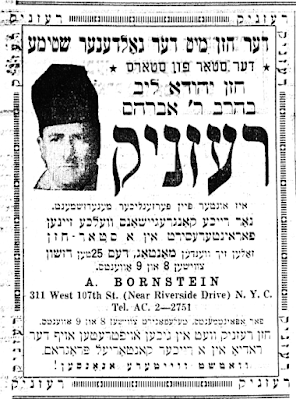

After occupying 311 West 107th Street for more than four decades, Regina Franke Steindler died in 1943. Her estate sold the property in February 1944 to Rabbi A. Bornstein. A renovation completed in 1955 resulted in an apartment "for rabbi's study," as described by Department of Buildings, and a kitchen on the first floor, two apartments on the second, and apartments and furnished rooms on the upper floors.

Among the tenants in 1964 was 19-year-old Columbia student Steven Galper. He was one of eight civil rights demonstrators arrested on March 20. Sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality, 50 demonstrators appeared at the F. & M. Schaefer Brewing Company in Brooklyn to protest alleged racial discrimination in hiring. Galper paid a $25 fine rather than spending five days in jail.

In September 1966, two other Columbia students, Paul Auster and Peter Schubert, moved into an apartment together. The two were best friends, according to Auster. In his Groundwork, Autobiographical Writings 1979-2012, Auster described the space as, "A two-room apartment on the third floor of a four-story walkup between Broadway and Riverside Drive." Referring himself in the second person, he writes:

A derelict, ill-designed shit hole, with nothing in its favor but the low rent and the fact that there were two entrance doors. The first opened onto the larger room, which served as your bedroom and workroom, as well as the kitchen, dining room, and living room. The second opened onto a narrow hallway that ran parallel to the first room and led to a small cell in the back, which served as Peter's bedroom. The two of you were lamentable housekeepers, the place was filthy, the kitchen sink clogged again and again, the appliances were older than you were and hardly functioned, dust mice grew fat on the threadbare carpet, and little by little the two of you turned the hovel you had rented into a malodorous slum.

Nevertheless, Paul Auster emerged as a novelist, poet and filmmaker. Among his works are the 1987 The New York Trilogy; The Brooklyn Follies, released in 2005; and the 2012 Winter Journal.

Edward and Regina Steindler's dining room is now part of a two-room apartment. image via sovereignrealestate.com

Another renovation was finished in 1972. There are nine apartments within the building. Despite the alterations, much of Clarence F. True's 1898 interior details survive.

photographs by the author

many thanks to historian Anthony Bellov for suggesting this post

_.jpeg)

.png)